Pleiotropy

from Greek πλείων pleion,

'more'

and τρόπος tropos,

'way'

Today’s post introduces a new term –

SGLT2.

Depending how old you are, you will be

aware of the term BFF – Best Friend Forever.

These days you can have several BFFs, not just one.

Pleiotropy (play-o-tropy) is a rather

nice sounding word that was brought into use in science and medicine by a

German geneticist Ludwig Plate in 1910. Pleiotropic effects of a drug are any beneficial

secondary effects.

Statins are the classic example. They

were developed to lower cholesterol, but many of the positive effects

experienced by users have nothing to do with cholesterol, they lower

inflammation (and more besides). It is now thought that inflammation in your arteries triggers a protective layer of cholesterol to be deposited. As the decades pass, this protective layer grows and ends up causing all kinds of problems.

When you repurpose an old drug for a

new use, you are taking advantage of its pleiotropic effects. For readers of this blog pleiotropy is a

friend, and quite possibly a BFF.

SGLT2

Today we look at repurposing a class

of drugs that lowers blood sugar for those with type 2 diabetes to treat a wide

range of brain disorders.

We also look at a cheap pain killer

that can be used to disrupt an inflammatory pathway key to most brain disorders

and even some cancers.

Our reader Eszter did recently highlight a very well written paper

about the potential to repurpose SGLT2 inhibitors to treat autism.

Eszter knows a lot about neurology, I should point out.

Eszter

has previously commented on the interesting overlap between drugs that provide

a benefit in Alzheimer’s and those that benefit some autism. She will likely find the link at the very end of this post of interest.

Repurposing SGLT2 Inhibitors for Neurological

Disorders: A Focus on the Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a

neurodevelopmental disorder with a substantially increasing incidence rate. It

is characterized by repetitive behavior, learning difficulties, deficits in

social communication, and interactions. Numerous medications, dietary

supplements, and behavioral treatments have been recommended for the management

of this condition, however, there is no cure yet. Recent studies have examined

the therapeutic potential of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2)

inhibitors in neurodevelopmental diseases, based on their proved

anti-inflammatory effects, such as downregulating the expression of several

proteins, including the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), interleukin-6

(IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), tumor necrosis

factor alpha (TNF-α), and the monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1).

Furthermore, numerous previous studies revealed the potential of the SGLT2

inhibitors to provide antioxidant effects, due to their ability to reduce the

generation of free radicals and upregulating the antioxidant systems, such as

glutathione (GSH) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), while crossing the blood

brain barrier (BBB). These

properties have led to significant improvements in the neurologic outcomes of

multiple experimental disease models, including cerebral oxidative stress in

diabetes mellitus and ischemic stroke, Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's

disease (PD), and epilepsy. Such diseases have mutual biomarkers with

ASD, which potentially could be a link to fill the gap of the literature

studying the potential of repurposing the SGLT2 inhibitors' use in ameliorating

the symptoms of ASD. This review will look at the impact of the SGLT2

inhibitors on neurodevelopmental disorders on the various models, including

humans, rats, and mice, with a focus on the SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin.

Furthermore, this review will discuss how SGLT2 inhibitors regulate the ASD

biomarkers, based on the clinical evidence supporting their functions as

antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents capable of crossing the blood-brain

barrier (BBB).

Recently I was asked by one researcher

reader where is the evidence to support my suggestion that Ponstan (Mefenamic

Acid) can enhance cognition. I was not

sure that I would find evidence that relates to actual humans, but I did. This

took me back to the time this blog looked into the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Just like the new generation of type 2

diabetes drugs have pleiotropic effects on the brain, so do Fenamate class

NSAIDs, specifically Ponstan.

There are four SGLT2 inhibitors approved to treat type 2 diabetes

·

Invokana

(canagliflozin)

·

Farxiga

(dapagliflozin)

·

Jardiance

(empagliflozin)

·

Steglatro

(ertugliflozin)

To be effective inside the brain such

a drug would need to be small and lipid (fat soluble) enough to get across the

blood brain barrier.

If the idea of a diabetes drug helping

brain disorders sounds strange, consider what we have already come across in

previous posts in this blog.

Other Type 2

drugs with pleiotropic effects

Metformin

Metformin was discovered exactly 100

years ago, in 1922. It is not a new drug

and it is the world’s most common therapy for type 2 diabetes.

It has been suggested metformin can

delay the onset of aging and also the onset and development of Alzheimer’s.

The use

of metformin has repeatedly associated with the decreased risk of the

occurrence of various types of cancers, especially of the pancreas and colon

and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Metformin

has been shown to raise IQ in children with Fragile-X syndrome by about 10%.

Some

people with autism do take metformin, in others it provides no benefit.

Glitazones

Glitazones

are a class of anti-diabetic drug that started to get popular from the year

2000. They work by stimulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

gamma (PPAR-γ) receptor. They will activate PGC-1 alpha, which we know is the key

regulator of mitochondrial

biogenesis. For some strange reason, glitazone drugs are not used to treat

mitochondrial disease.

Glitazones

have broad anti-inflammatory pleiotropic effects.

Pioglitazone

has been researched in autism and I have used it for several years as a spring

and summertime add-on therapy in Monty’s PolyPill.

Back to Eszter’s

paper

I highlight some of the tables, which

do summarize the beneficial effects.

Inflammatory signals promote inflammation by

activating the microglia and astrocytes within the brain in ASD. SGLT2

inhibitors influence on the inflammation and neuroinflammation, SGLT2 inhibitors decrease the

inflammatory factors levels, such as the M1 macrophages, STAT1 inflammatory

transcription factor, cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor

(TNF-α), and vascular cell adhesion protein (VCAM) in neurodevelopmental

diseases

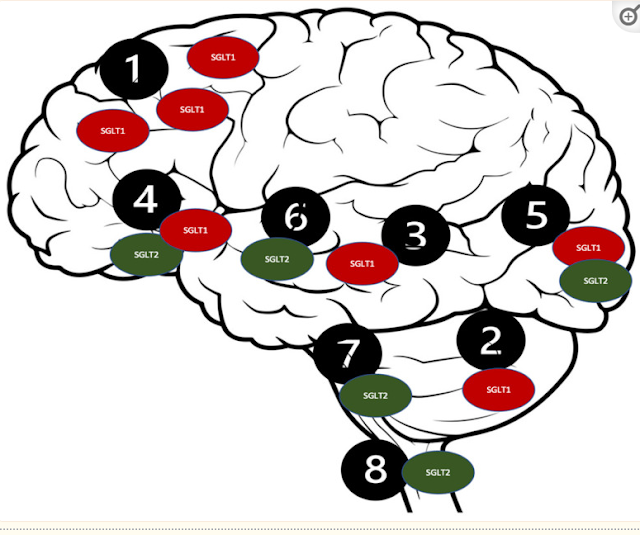

Distribution of the SGLT receptors in the

CNS. 1. Brain cortex (pyramidal cells); 2. Purkinje neurons; 3. Hippocampus; 4.

Hypothalamus; 5. Micro vessels; 6. Amygdala cells; 7. Periaqueductal gray; 8.

Dorsomedial medulla.

Such a

distribution of the SGLT2 receptors [114] could

potentially be responsible for their intriguing neuroprotective qualities,

which could be beneficial in several neurological disorders, including ASD [99]. The SGLT2

inhibitors’ proposed mechanisms are presented in Figure

3. The

antioxidant effect of the SGLT2 inhibitors can be attributed to their

stimulatory action on the nuclear factor erythroid 2 (Nrf2)- related factor 2

pathway [115]. This

displays the antioxidant activity because of their genetic expression of the

antioxidant proteins, including glutathione-s-transferase (GST), SOD, and NADPH

quinone dehydrogenase-1 to protect against cellular apoptosis [116]. The

anti-inflammatory characteristics of the SGLT2 inhibitors could be accredited

to the downregulation of NF-KB, which decreases IL-1β and the TNF-α expression

[117].

Empagliflozin has the highest selectivity for the SGLT2 receptors (2500-fold)

when compared to dapagliflozin which has (1200-fold) selectivity, and

canagliflozin (250-fold) [118,119]. Therefore, in the context of the

neuroprotective effects associated with the SGLT1 and SGLT2 receptors’

inhibition, canagliflozin was hypothetically preferred over other SGLT2

inhibitors, due to its dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibition capability [120].

SGLT2 inhibitors have the potential to

improve ASD patients’ behavioral and brain disruptions by increasing the

cerebral brain derived neurotrophic factor and reducing the cerebral oxidative

stress, including elevated the GSH and catalase activity, reduced MDA, amyloid

β levels, plaque density, and acetylcholinesterase

ASD

remains a global health dilemma, as it is a chronic condition, and is

incurable, leading to a reduced quality of life. It is crucial to find the

mutual molecular mechanisms of ASD and redefine the indications for the

well-studied medication with numerous pleiotropic effects to find a solution.

This review has disclosed the impact of the SGLT2 inhibitors in neurological

diseases, which could relate to ASD as it shares multiple pathways and mutual

biomarkers. SGLT2 inhibitors display several neuroprotective properties,

highlighting their therapeutic potential for ASD patients, as these agents have

the capability to inhibit the acetylcholinesterase enzyme, reduce the elevated

levels of the oxidative stress in the brain, and restore the anabolism and

catabolism balance. Moreover, clinical intervention studies are vital to

determine whether the displayed methods are useful as the SGLT2 inhibitors have

never been tested on ASD directly. Currently, our research team is conducting a

preclinical experiment to assess the effects of canagliflozin on the

VPA-induced ASD in Wistar rats.

Back to the NLRP3

Inflammasome

Ponstan (Mefenamic acid) is one of the

few available drugs that is known to be a potent inhibitor of an inflammatory

pathway called the NLRP3 inflammasome. It

is mainly present macrophages, a type of white blood cell in the immune system. The role of macrophages includes gobbling up

pathogens.

In the brain the microglia

are the resident macrophages. The

microglia have multiple functions in the brain and we know that in autism they

can be stuck in an overactivated state and then do not fulfil their other functions.

In many diseases activation of the NLRP3

inflammasome in local macrophages occurs.

Inhibiting this process can disrupt the disease process.

My guess is that this is the mechanism

by which Ponstan is improving cognition in some of the people with autism who

are taking it.

In the paper below we see that people

taking Ponstan to treat their prostate cancer (PCa) experience an improvement

in their cognition.

Inflammation

is an essential component of prostate cancer (PCa), and mefenamic acid has been

reported to decrease its biochemical progression. The current standard therapy for PCa is

androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), which has side effects such as cognitive

dysfunction, risk of Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia. Published results of in

vitro tests and animal models studies have shown that mefenamic acid could be

used as a neuroprotector. Objective: Examine the therapeutic potential of mefenamic acid in cognitive

impairment used in a controlled clinical trial. Clinical trial phase II

was conducted on patients undergoing ADT for PCa. Two groups of 14 patients

were included. One was treated with a placebo, while the other received

mefenamic acid 500 mg PO every 12hrs for six months. The outcome was evaluated

through the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score at six months. At the

beginning of the study, both groups had similar MMSE scores (mefenamic acid vs.

placebo: 26.0±2.5 vs. 27.0±2.6, P=0.282). The mefenamic acid group improved its

MMSE score after six months compared with the placebo group (27.7±1.8 vs.

25.5±4.2, P=0.037). Treatment

with mefenamic acid significantly increases the probability of maintained or

raised cognitive function compared to placebo (92% vs. 42.9%, RR=2.2,

95% CI: 1.16-4.03, NNT=2.0, 95% CI: 1.26-4.81, P=0.014). Furthermore, 42.9% of

the placebo group patients had relevant cognitive decline (a 2-point decrease

in the MMSE score), while in patients treated with mefenamic acid, cognitive

impairment was not present. This

study is the first conducted on humans that suggests that mefenamic acid

protects against cognitive decline.

In the AEA mouse model of MS (multiple

sclerosis) we see the role again of NLRP3 on cognition.

Some studies have indicated that NLRP3 inflammasome activation is

involved in mediating synaptic dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and

microglial dysfunction in AD models, and that the inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome

attenuates spatial memory impairment and enhances Aβ clearance in AD

model. However, there is no research on NLRP3 inflammasome in MS-related

cognitive deficits. In our study, we found that microglia and NLRP3 inflammasome were activated in the

hippocampus of EAE mice, while pretreatment with MCC950 inhibited the

activation of microglia and NLRP3 inflammasome

Again, we see a benefit from

inhibiting NLRP3 in Alzheimer’s.

Aberrant activation of the Nod-like receptor

family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome plays an essential role

in multiple diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and psoriasis. We

report a novel small-molecule inhibitor, NLRP3-inhibitory compound 7 (NIC7),

and its derivative, which inhibit NLRP3-mediated activation of caspase 1 along

with the secretion of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-18, and lactate dehydrogenase. We

examined the therapeutic potential of NIC7 in a disease model of AD by

analyzing its effect on cognitive impairment as well as the expression of

dopamine receptors and neuronal markers. NIC7 significantly reversed the

associated disease symptoms in the mice model. On the other hand, NIC7 did not

reverse the disease symptoms in the imiquimod (IMQ)-induced disease model of

psoriasis. This indicates that IMQ-based psoriasis is independent of NLRP3.

Overall, NIC7 and its derivative have therapeutic prospects to treat AD or

NLRP3-mediated diseases.

What about sepsis (blood poisoning)?

The

pathophysiology of sepsis may involve the activation of the NOD-type receptor

containing the pyrin-3 domain (NLPR-3), mitochondrial and oxidative damages. One of the

primary essential oxidation products is 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG), and its

accumulation in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) induces cell dysfunction and death,

leading to the hypothesis that mtDNA integrity is crucial for maintaining neuronal

function during sepsis. In sepsis, the modulation of NLRP-3 activation is

critical, and mefenamic

acid (MFA) is a potent drug that can reduce inflammasome activity, attenuating

the acute cerebral inflammatory process. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate

the administration of MFA and its implications for the reduction of

inflammatory parameters and mitochondrial damage in animals submitted to

polymicrobial sepsis. To test our hypothesis, adult male Wistar rats were

submitted to the cecal ligation and perforation (CLP) model for sepsis

induction and after receiving an injection of MFA (doses of 10, 30, and

50 mg/kg) or sterile saline (1 mL/kg). At 24 h after sepsis

induction, the frontal cortex and hippocampus were dissected to analyze the

levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-18; oxidative damage (thiobarbituric acid

reactive substances (TBARS), carbonyl, and DCF-DA (oxidative parameters);

protein expression (mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), NLRP-3,

8-oxoG; Bax, Bcl-2 and (ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA-1));

and the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes. It was observed

that the septic group in both structures studied showed an increase in

proinflammatory cytokines mediated by increased activity in NLRP-3, with more significant

oxidative damage and higher production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by

mitochondria. Damage to mtDNA it was also observed with an increase in 8-oxoG

levels and lower levels of TFAM and NGF-1. In addition, this group had an

increase in pro-apoptotic proteins and IBA-1 positive cells. However, MFA at

doses of 30 and 50 mg/kg decreased inflammasome activity, reduced levels

of cytokines and oxidative damage, increased bioenergetic efficacy and reduced

production of ROS and 8-oxoG, and increased levels of TFAM, NGF-1, Bcl-2,

reducing microglial activation. As a result, it is suggested that MFA oinduces protection in the central

nervous system early after the onset of sepsis.

Conclusion

One reader of this blog attributes her

son’s autism to his sepsis (blood poisoning) at birth. It is pretty clear from

one of today’s papers that perhaps babies with sepsis should be treated with

Ponstan (Mefenamic acid) to prevent damage to their brain. I was recently contacted by another parent where sepsis occurred at birth.

I think the researchers make a strong

case that the pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibitors that benefit Alzheimer’s,

Parkinson’s and ALS very likely will also be beneficial in some autism. They plan to test canagliflozin on rats with

valproic acid-induced autism.

I have to say to Eszter that I

actually think inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome might be the Neurologist’s

best friend forever (BFF), perhaps even better than an SGLT2 inhibitor.

What is for sure is that both (SGLTi

and NLRP3i) should be subject of clinical trials in autism. I suggest going

straight humans rather than rats.

I have had positive feedback so far on

my suggestion that low dose (250 mg) Ponstan/Mefenamic acid could be an

effective long term autism therapy. We

do have to mention that Knut Wittkowski has patented its use in autism; he

proposed it as a preventive measure in 2-3 year olds to redirect severe

non-verbal autism towards Asperger’s. I selected it to treat extreme sound

sensitivity, but later witnessed its pleiotropic effects.

If anyone has experience on the use of

an SGLT2 inhibitor in autism, I would be very interested to read about it.

We should add Ponstan to the long list

of drugs in this autism blog that may be beneficial in MS (Multiple sclerosis).

(ALA, Clemastine, NAG, Ibudilast, DMF, Ponstan etc).

P.S.

A last word from

Google

Having noted my recent googling

activity, I was today sent the following news item by Google.

Harnessing the

Brain’s Immune Cells to Stave off Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative

Diseases

Researchers have identified a protein that

could be leveraged to help microglia in the brain stave off Alzheimer’s and

other neurodegenerative diseases

But how does SYK protect the nervous system

against damage and degeneration? We found that microglia use SYK to migrate

toward debris in the brain. It also helps microglia remove and destroy this

debris by stimulating other proteins involved in cleanup processes. These jobs

support the idea that SYK helps microglia protect the brain by charging them to

remove toxic materials.